Storytelling is the basic mode of human interaction and a fundamental way of acquiring knowledge, influencing attitudes and moderating behaviors.

This month’s “In Conversation” column spotlights Abiola Okubanjo, BSc, ACA, CEO and founder of Action On Blood, a health communication social enterprise dedicated to tackling global health inequalities and expanding blood donation and health engagement among underrepresented communities. She also serves as director of Sahara BioMedix, a biopharmaceutical company providing blood and blood components in Nigeria.

Leading these organizations, Okubanjo focuses on increasing blood, organ and stem cell donation among communities of color through community-driven engagement strategies, including storytelling-based campaigns, film projects and other creative outreach approaches.

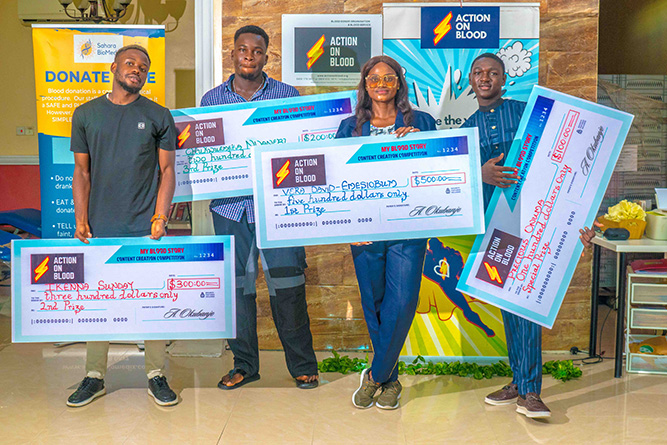

In May 2024, Action on Blood launched the “My Blood Story: Creative Content Competition” in partnership with Global Blood Fund (GBF) to amplify Lagos community members’ experiences with blood donation through social media storytelling. Okubanjo spoke with AABB News about how storytelling campaigns can increase blood donation in underrepresented communities and how blood centers can use co-designed content to engage more diverse donors.

One of our international partners, Global Blood Fund (the charity arm of Our Blood Institute, whose mission is to improve access to safe blood transfusions for countries and communities who need it most), reached out to us with the partnership idea. We would run the competition, and GBF would provide the digital platform for receiving entries and the prize monies.

We were excited about the opportunity as it gave us a chance to raise awareness about the importance of blood donation locally — what we have been doing for several years now — but on a much larger scale than we would have been able to do alone.

Using local stories was also very important as the context, names, places, etc. had to be ones that local people would recognize for the issue to be relatable. The reasons people in Lagos need blood and the challenges they face in getting it are very different to how things happen in America, Europe or even in another African country.

It was also important for us to give a voice to those that people often don’t hear from and to allow them to tell their stories in their own way. There was no doubt that we would get some creative pieces.

There was a sense of drama and tension to the stories you wouldn’t see in more high-income and better-resourced countries. However, I wouldn’t say that I was surprised by any of the stories themselves. Interacting with donors, recipients, family members and health care workers in Lagos, we hear these stories all the time, and they never fail to motivate us. So, we knew the stories would be emotional and motivate potential donors.

Campaigns like these are successful because of all the things people don’t see that have to happen in the background. You need to be clear about what you’re trying to achieve and if you have the right resources and partners to deliver that. In GBF, we had a partner that had run similar competitions before in America and other African countries and were keen to share their knowledge and expertise so that we could deliver the campaign in Lagos.

In Action on Blood, GBF had a local partner that already had the networks, understood the community and could “speak the local language.” We also had the resources, experience and technical capability to deliver a program to the quality and standard they needed. This enabled them to trust us, so they could step out of the way and allow us to do what we felt was right for our community.

The storytelling campaign revealed that it doesn’t matter what part of the world you live in, what language you speak or what culture you have, we are all motivated to donate because we love, we care, we have empathy and we want to do something when others are suffering. What might differ is how far the responsibility to help others in the community extends, and what that looks like.

A lot of the stories from this campaign focused on family members needing blood. That sense of family, which tends to extend beyond the Western concept of the nuclear family, is extraordinarily strong for Nigerians and other Black people; we’ve seen similar donating preferences in research we’ve conducted in the United Kingdom among Black African and Caribbean communities. It was really emotional reading entries about people losing loved ones due to a lack of blood, or parents having to go to extreme lengths trying to save their child. The impact on the wider family and community of someone needing blood is a major motivator for becoming a donor.

Almost every story had a sense of urgency or “do-or-die” to it. The health system is poorly funded, and there is very little blood available in the country, so most people’s experience of blood donation involves an emergency or major tragedy. With depressing regularity, entries demonstrated the role systemic context plays in lives being prematurely cut short. When angry and frustrated with situations that feel unjust and beyond individual control, people are driven to donate.

But these challenges can also have a negative effect on donor motivation. If people can’t be sure there will be enough blood to save them or their loved ones when needed, it is rational to want to preserve what little you have for those closest to you. When there is no safety net because health care is underfunded and blood availability is scarce, people have to look after their own.

This is why it is extremely difficult to mobilize voluntary donations beyond a person’s immediate circle when the system works against it.

To date, the medical field has tried to encourage donations using statistical evidence, probability, and appeals to logic and reason. As there is still a global shortage of blood — more so in certain communities — clearly these are not working to the extent we need them to.

We already know that facts often do not change people’s minds. In fact, people tend to only use facts to support already held beliefs. A substantial body of evidence from cognitive psychology, neuroscience, marketing, and other fields has shown this.

What we do know works is stories. Storytelling is the basic mode of human interaction and a fundamental way of acquiring knowledge, influencing attitudes and moderating behaviors. People have been telling each other stories for millennia.

From my experience with blood donation, telling real stories allows us to tap into a shared humanity. The stories bypass a person’s critical reasoning and go to the subconscious, which we know exerts a much bigger influence on behavior. People can argue with facts and figures, but it is much harder to argue with a feeling incited by a story.

Blood centers should seek to work genuinely with partner organizations that have the skill to deliver the content and the ability to navigate the culture and understand the nuances. It takes humility to know what you are good at (e.g., administering blood) and what isn’t your area of expertise (e.g., convincing an underrepresented group to change their attitudes and behaviors). Then, it takes trust to give those that can do the bits you can’t do the freedom — and resources — to get on with it.

At Action on Blood, we have been able to develop content for different communities (e.g., Africans vs. Caribbeans) and different groups within communities (e.g., new migrants vs. second-, third-, and fourth-generation migrants) and different ages (e.g., older vs. younger) by doing just that. Recognizing that people are not homogenous, we go out to the specific community we are targeting and ask professionals and non-professionals to be involved in our creative process. We do that every single time we have a new audience.

We all feel scared at times, experience moments when the floor drops from under our feet, love our families and want to laugh at the absurdities of life. By shining a light on our shared humanity, blood centers can use storytelling campaigns to attract new donors without alienating the majority.

For example, there was a documentary that came out a few years ago that had good intentions to empower young Congolese filmmakers to tell their stories. However, questions arose about the perspective of the film itself, as it was a Dutch filmmaker who documented their journey of self-representation. The participants voiced concerns that by focusing on certain parts of their narratives or showing certain visuals, the director maintained the stereotypes they were keen to dispel. When it comes to storytelling, you have to let the community tell their own story. It must be from their viewpoint and not the gaze of an outsider.

To be effective, community-led interventions should be authentic and equitable collaborations between stakeholders—otherwise it risks being tokenism. It isn’t enough to find someone internally who is from that culture and expect them to be the voice for their whole community.

Organizations will need to get out of the way a little bit and not want to control the whole process. To do this, they will have to take the time to find professional community partners that can work with their institutional idiosyncrasies and who know what they are doing.

From the outset, organizations should be prepared for the fact that it will take longer and probably cost more than calling in a standard film production company that has no community engagement resources or experience. That might involve a bit more internal politicking and convincing, but we have proved that when done properly, the payoffs can be significant.

By enhancing trust and engaging people emotionally, arts-based approaches can improve donor recruitment. Through the co-creation of the four community films project, our study showed the effectiveness of film-based arts approaches in positively affecting the target audience and, importantly, generalizing this positive impact to non-target audiences.

Within the community sample they were designed for, the community films were all highly evaluated and valued. Participants showed a high willingness to donate after watching these films, with particularly positive emotional responses to one of the films. Within a wider non-target population, three of the community films and the NHS Blood & Transplant x Marvel’s Black Panther collaboration were positively received in terms of propensity to donate in both Black and White samples, as well as emotional engagement.

I’m hopeful that the approaches we have demonstrated will improve the volume and diversity of blood donors from underrepresented and majority communities. However, as we have shared our findings with blood centers from different countries that operate in different contexts, we often hear that donor recruitment teams sometimes struggle to positively present the cost-benefit analysis of developing content for target audiences within their organizations.

The push-back can be, “If we are already getting sufficient volumes of blood from our main demographic, why should we expend energy on marginal groups?” or “Would targeting one particular group upset or exclude the majority population?” When budgets are also tight, it’s very difficult to overcome such concerns and affect the status quo.

However, that kind of thinking is short-sighted and perpetuates inequalities. Blood centers benefit clinically, operationally and ethically from recruiting donors from marginalized groups, even when current volumes seem “sufficient” or costs may be higher. Many blood components work best when the donor and recipient share similar genetic and ethnic backgrounds, and relying heavily on one main demographic is risky. Aging donor pools and demographic shifts mean today’s “sufficient” supply may become tomorrow’s shortfall if new, younger and more diverse donors are not brought in now.

There is also an ethical and social responsibility issue to consider. Narrow demographics can potentially concentrate certain blood groups and underrepresent others, leaving some patients struggling to find suitable matches even when shelves seem full. These disparities represent a shortage not just of blood itself but of fair access to lifesaving treatment for patients whose backgrounds are poorly represented in the donor pool. Proactive work with marginalized donors aligns with the principles of justice and non-discrimination in health care, reinforcing that the system values every patient and every community.

We are continuing our work tackling health inequities in areas the public can get involved through donation. In the U.K., we are using our insights with minority communities to source ethnically diverse research participants for clinical research. Modern biomedical research, such as genomics studies, requires tens or even hundreds of thousands of participants, yet researchers often lack adequate access to ethnically diverse biospecimens or accompanying demographic and health data. We are helping researchers in the U.K. and elsewhere to overcome this barrier.

In Nigeria, there is still much to do to establish a culture of voluntary blood donation and enable a sufficient and safe blood supply in a sustainable way. The logistical and operational challenges are significant, with high financial implications. Smaller organizations like ours face considerable obstacles, and progress is slower than we would like. But we persevere, with the stories we encounter every day motivating us to keep going.

Transfusion is AABB’s scholarly, peer-reviewed monthly journal, publishing the latest on technological advances, clinical research and controversial issues related to transfusion medicine, blood banking, biotherapies and tissue transplantation. Access of Transfusion is free to all AABB members.

Learn More About Transfusion Journal

Keep abreast of what's happening in the field of biotherapies with CellSource - AABB's monthly update on the latest biotherapies news.

To submit news about the blood and biotherapies field to AABB, please email news@aabb.org.

President

Meghan Delaney, DO, MPH

Chief Executive Officer

Debra Ben Avram, FASAE, CAE

Chief Communications and Engagement Officer

Julia Zimmerman

Director of Marketing and Communications

Jay Lewis, MPH

Managing Editor

Kendra Y. Mims, MFA

Senior Communications Manager

Drew Case

AABB News

(ISSN 1523939X) is published monthly, except for the combined November/December issue for the members of AABB; 4550 Montgomery Avenue; Suite 700 North Tower; Bethesda, MD 20814.

AABB is an international, not-for-profit association representing individuals and institutions involved in transfusion medicine, cellular therapies and patient blood management. The association is committed to improving health by developing and delivering standards, accreditation and educational programs that focus on optimizing patient and donor care and safety.

+1.301.907.6977

Email: news@aabb.org

Website: www.aabb.org

Copyright 2025 by AABB.

Views and opinions expressed in AABB News are not necessarily endorsed by AABB unless expressly stated.

Notice to Copiers: Reproduction in whole or part is strictly prohibited unless written permission has been granted by the publisher. AABB members need not obtain prior permission if proper credit is given.